If James Bond (or Jason Bourne, if you’re being patriotic) were a bankruptcy and restructuring lawyer, he’d love this ruling. It’s just a shame it wasn’t a proceeding under chapter 007. In a recent decision out of the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York, Awal Bank, a Bahraini financial institution in administration, was permitted to file its Schedules of Assets and Liabilities and Statement of Financial Affairs (referred to typically as the “schedules and SOFAs”) without the specific creditor claim information that is typically disclosed in chapter 11 cases pursuant to section 521 of the Bankruptcy Code. Section 521(a)(1) provides that debtors shall file a list of creditors and, unless the court orders otherwise, a statement of assets and liabilities, and this information typically includes specific information about the amount owed to known creditors of a debtor.

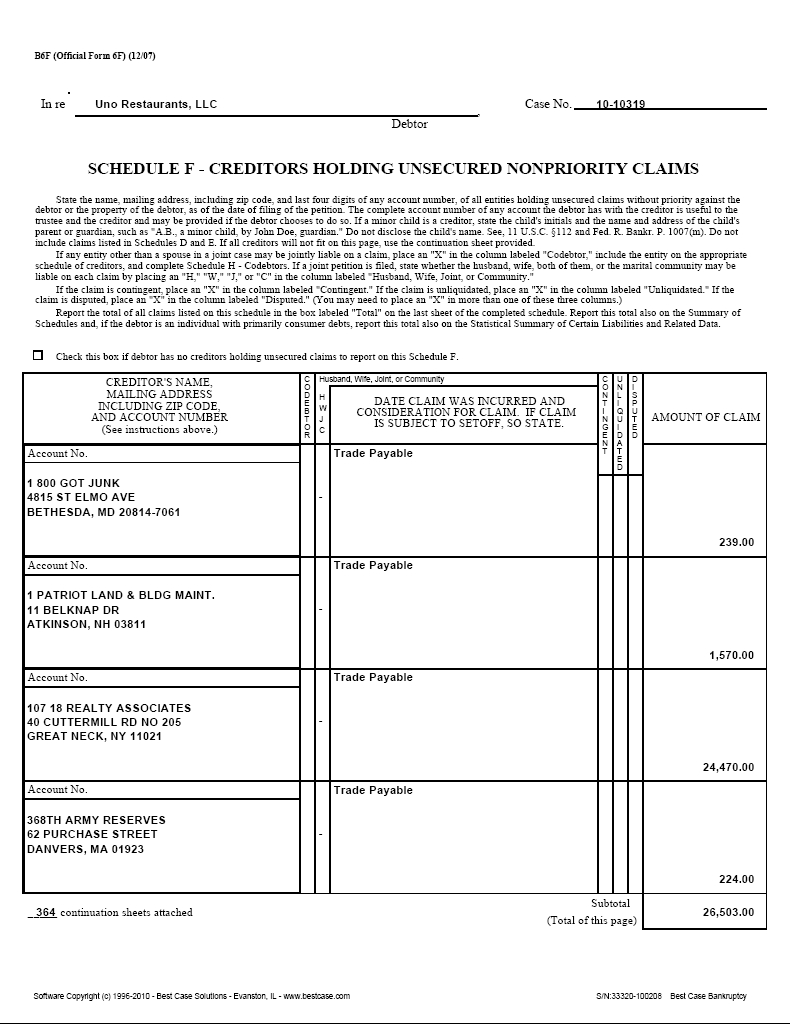

For those of you who aren’t so(fa) inclined, here’s what schedules might ordinarily look like. Schedule F (Creditors Holding Unsecured Nonpriority Claims) typically includes the name and address of the creditor, the type of claim and when filed, and the amount of the claim as recorded in a debtor’s book and records.

Awal Bank had been placed into administration in Bahrain in on July 30, 2009. As part of the Bahraini administration, a protocol was put in place whereby creditors asserting a claim against Awal Bank were (and continue to be) permitted to attend quarterly meetings with the external administrator for updates on the status of the administration of the bank’s assets, upon the signing of a confidentiality agreement.

Shortly before Awal Bank was placed under Bahraini administration, a derivative contract was closed out, with Awal Bank being owed approximately $13 million by its counterparty. Awal Bank issued instructions for these funds to be transferred to its account with the Bank of Bahrain and Kuwait. The financial institution transferring the funds mistakenly transferred the outstanding balance on the derivative contract to Awal Bank’s U.S. account with HSBC, instead of following its original instructions. This mistake was unfortunate, as Awal Bank owed HSBC approximately $75 million under a credit facility that had been terminated, and HSBC promptly used these funds to set off what it was owed under the credit facility.

In a bid to have these funds returned, the external administrator applied for and received recognition of the Bahraini administration as a foreign main proceeding in a chapter 15 case filed in the Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York. Subsequently, though, it filed a chapter 11 case as a measure of caution to remove any doubt as to its authority to pursue avoidance actions under the Bankruptcy Code. (Interestingly, while a recognized foreign representative may choose to commence a case under chapter 11 if the debtor has assets or business operations in the United States, it is often unlikely to do so given the extent of the relief available under chapter 15 and the more burdensome requirements, including disclosure requirements, imposed by chapter 11. Pursuant to section 1521(a)(7) of the Bankruptcy Code, however, a court cannot authorize a foreign representative to exercise the power to bring avoidance actions under sections 522, 544, 545, 547, 548, 550, and 724(a) of the Bankruptcy Code, leaving a foreign representative with the need to file a chapter 11 case to pursue such avoidance actions).

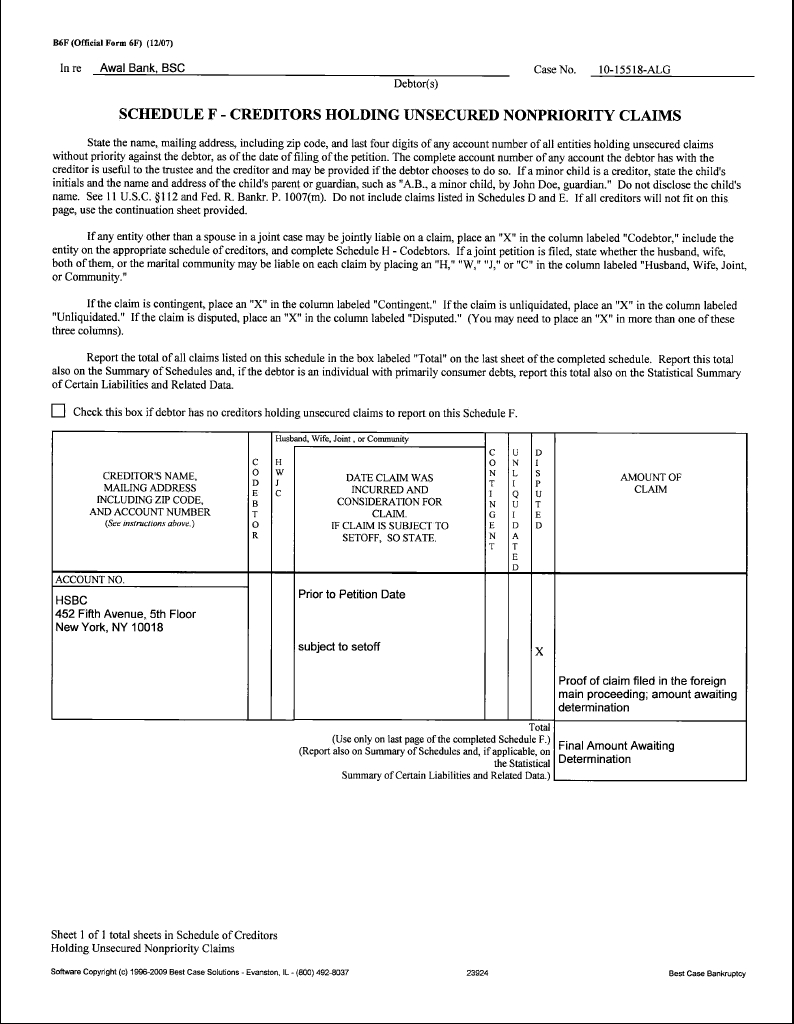

Upon its chapter 11 filing, Awal Bank filed a motion seeking relief from certain disclosure requirements of section 521 of the Bankruptcy Code. While there is no statutory guidance specifying what circumstances allow a party to avoid the disclosure requirements of section 521(a)(1)(B), there is precedent for such limited disclosure in prepacks, for instance, where general unsecured creditors are typically unimpaired, and affected creditors have already voted. Awal Bank subsequently withdrew the motion when the court required that additional notice be given to creditors before the requested relief could be considered, and then filed its schedules and SOFAs. As you can see below, these schedules and SOFAs were a source of controversy. The only unsecured creditor listed was HSBC, and the filings were later characterized by HSBC in a motion to dismiss the Awal chapter 11 case as being “a parody of the disclosures required by and commonly filed in chapter 11 bankruptcy cases.”

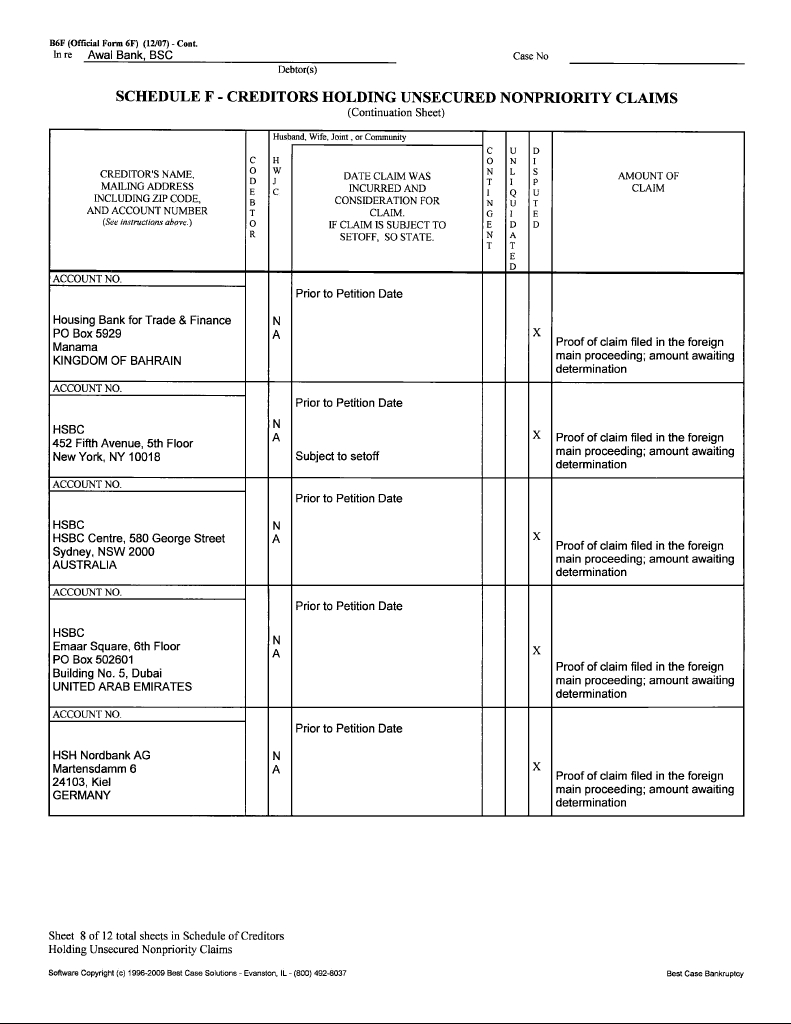

This, unsurprisingly, drew the scrutiny of the U.S. Trustee, which predictably requested that these filings be supplemented. Awal Bank subsequently filed a motion seeking permission to file schedules that disclosed its existing creditors, but omitted specific claim amounts. Awal Bank’s external administrator argued that because the sole purpose of its chapter 11 case was to attempt to recover the incorrectly wired funds from HSBC, its chapter 11 and chapter 15 cases should be coordinated with its Bahraini proceedings, and the limited disclosure should be permitted. In broad terms, Awal Bank argued that the confidentiality protocol in place in Bahrain in the foreign main proceeding should give the court sufficient grounds to waive the section 521 disclosure requirements. While these various motions were pending, Awal Bank supplemented its existing disclosure with amended schedules detailing, as you can see below, the existence of both U.S. and non-U.S. liabilities, but omitting specific claim amounts.

Ruling that significant factors weighed in favour of granting Awal Bank’s request, the court found that further section 521 disclosure would be disruptive to the administration of the Bahraini case, as creditors had already provided the relevant information with an expectation of confidentiality and would have access to such information if they followed the existing Bahrain protocol. Considering that the amended schedules provided most of the information normally provided in such documents, apart from specific creditor claim amounts, and that HSBC had not identified any specific need for the disclosure it was seeking, the court found that good cause existed to modify the debtor’s obligations under section 521(a). In doing so, the court was required to proceed with a detailed analysis of the nature and purpose of a plenary case filed by a foreign representative, after obtaining recognition in a chapter 15 ancillary proceeding, which will form the subject of a separate blog post. Awal Bank took the scenic route in fulfilling its section 521 disclosure obligations, but got there in the end, with its confidentiality and disclosure strategy shaken, but not stirred.

Contributor(s)